|

About me, the traveler

Travelogues

Trip 1 - India, Nepal, and China

Trip 2 - Southeast Asia

Trip 3 - Mongolia to Eastern Europe

Trip 4 - Middle South America

Trip 5 - Southern Africa

Trip 6 - Scandinavia, the Baltics, and Greenland

Trip 7 - The Balkans

Trip 8 - Morocco and Southern Spain

Trip 9 - Western India

Trip 10 - Outer Indochina

Trip 11 - Ethiopia and Dubai

Trip 12 - Iceland

Trip 13 - Japan

Trip 14 - Caucasus

Trip 15 - Central & East Asia

Trip 16 - Inner Indochina and Japan Tales From the Tour (a running travelogue)

Top-five lists

New York City excursions

Cheap East Coast bus alternatives

Links

|

Trip 3 - Mongolia to Eastern Europe

Part 2: Russia (24 Sep to 6 Oct 1999)

Exchange rate: US$1 = 25 Russian rubles (RUB)

24 Sep–28 Sep

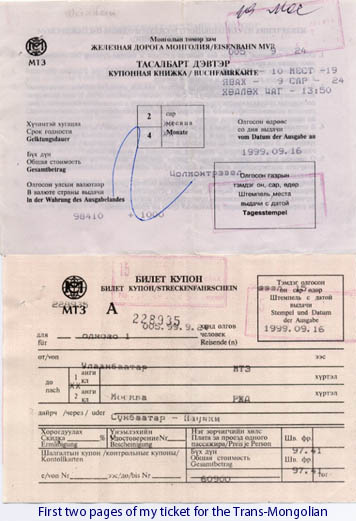

Train: Trans-Mongolian #5, Ulaanbaatar to Moscow

(13:50; 102h 48m; arrived 10m late)

|

The departure of a long-distance train is a remarkably emotional experience, both for those aboard and for those watching it leave. It's even more emotional when most of the passengers are embarking on a four-day trip. What will your compartment-mates be like? Will you meet anyone who speaks your language? What's the purpose of everyone's journey? Is there anyone you should stay away from? Better yet, is there anyone you'll keep in touch with after the journey

ends?

I was in car 10, compartment 9, berth 19 - a lower berth, which is what I'd requested. I was the first to arrive in that compartment; a man named Khui joined me a few minutes

later.

I set out to explore the train and find the dining car. The four-berth compartments were on one side of the train; a corridor, which doubled as a meeting place (and, at stations, a selling area), ran along the other. Posted in the corridor was the train schedule: We'd have five or six stops a day, usually for 10 to 30 minutes each, so there'd be ample time for disembarking for a few minutes every so often. I didn't find the dining car - they didn't add it until we entered

Russia.

When I returned to my compartment, Khui had gone. In his place were three Mongolians who would be my compartment-mates for the next four days: Batsukh, Pakyet, and Amrah. They were members of the Mongolian police force, part of a group of six on the way to Turkey for a conference on narcotics (they'd fly from Moscow to Turkey). They also had some souvenirs (miniature horse-head fiddles and the like) for sale. They were some of the friendliest people I'd ever met on a trip. And since Batsukh and Pakyet spoke fluent Russian, we could, for the most part,

communicate.

In compartment 10 were three women: Robyn, from England, and Sam and Guie, two Australians. Robyn was finishing a trip through Asia and would end her vacation with five days in Moscow; Sam and Guie had been traveling for five months in Laos, China, and Thailand and would spend just two days in Moscow before heading to England to get work permits. Then they'd head for Israel to work on a kibbutz. Rounding out their compartment was a Mongolian of whom they were not too fond, owing to his excessive, strewn-about

luggage.

The train took us through the fairly deserted Mongolian countryside. We saw distant mountains, the occasional ger, and plenty of cows. There were fences on both sides of the train tracks to keep the animals out. Our first stop was near nightfall, in Darkhan, where I bought toilet paper, water, and Pepsi. Pakyet said, "That's not real Pepsi." He was right - it was the most vile drink I'd ever tasted. He eventually through it out the window with other trash, as was the custom. I was glad to be rid of

it.

Mongolian customs, at Sükhbaatar, was fairly straightforward, but crossing into Russia was a bit more complex. Many passengers spend much of their lives on this train, selling Mongolian coats and hats and other goods along the platforms in Russia and loading up on Russian goods in Moscow. So many of them have lots of luggage. We spent several hours at Naushki, the Russian border post - and when the train is stopped, the bathrooms are closed, because the toilet bowl drains directly onto the tracks and the locals don't want their train stations continually fertilized. I talked a bit with Robyn, Sam, and Guie during the long wait, and as we looked out at an enormous collection of luggage waiting customs inspection, I asked what it must be like to be married to a customs official. They replied that it must be rather dreary. Finally the train started up again, and we set our watches back four hours, because though we were thousands of kilometers east of Moscow, all Russian trains run on Moscow

time.

And because Russian trains run on Moscow time, sunrise was at 3:30 in the morning, which is when we reached Ulan-Ude (two hours late because of the delay in Naushki). Ulan-Ude is where the Trans-Mongolian Railway meets up with the main Trans-Siberian Railway line, which runs from Moscow to Vladivostok, on the Pacific coast.

After we left Ulan-Ude, I had a little sausage and cheese and then went back to sleep, waking up a couple of hours later as the train worked its way through valleys and around the beautiful Lake Baikal. At the lakeside down of Sludyansk, people on the platform sold freshly caught, salted, ready-to-eat fish, and I lamented the fact that I didn't have any rubles with which to buy one. I spent the day playing Uno with the Australian and English passengers in the next compartment, talking with the Mongolians in my own, and generally being very pleased with a lifestyle of snacking, sleeping, card playing, and looking out at the countryside. At one point I changed money in the dining car by paying for a snack in dollars and receiving change in rubles. Later on, the Mongolians and I shared food as the scenery became more lush, with the birch trees for which Siberia is so famous. We passed few towns of any significant size, and it occurred to me that one reason many Siberians drink themselves silly is that there is simply nothing else to do. Sunset was at 16:00 and the dining car closed two hours

later.

Sunrise the next day was also around 3:30, and shortly thereafter we arrived in Marinsk, where I was finally able to buy a salted fish on the platform. Guie and I and my compartment-mates shared it, though it was not to Pakyet's liking. It began to snow - a sight Sam had never seen - and I joined Sam, Guie, and Robyn in the dining car, where I taught them blackball (a card game similar to spades) and had eggs. Later on, I taught the game to my Mongolian friends, and Guie joined us for some conversation. I got to translate between Russian and English - a job that I much enjoyed, at least for an hour or two. As we approached Novosibirsk, the scantily inhabited countryside became more suburban, with regularly placed, well-built one-story houses. Instead of birches, the vegetation was greener. In the mid-afternoon, my compartment-mates and the travelers accompanying them had something of a vodka seance in our compartment. I'm not sure what secrets they were discussing, but I let them have the place to

themselves.

Tyumen was a big station that we reached at 4:45 the next morning; there was much buying and selling going on between the passengers and those on the platform. When we left, everyone remained awake, and the Mongolians had their first drinks of the day. They invited me to join in, but while I was there physically, I couldn't stomach more than a tiny sip of beer at that hour. The Mongolians disappeared for much of the day; I played spit with my English-speaking companions and then played spades with Robyn. I read

Riding the Iron Rooster for part of the afternoon; it seemed

appropriate.

Robyn, Sam, and Guie invited me to a little party in their compartment for our last night. To prepare, we bought some vodka in Perm (a well-placed vendor offered it to us after we had inquired at a kiosk whether there was any for sale). After a couple of hours there, I went two doors down, where I met Khui and a bunch of other Mongolians with whom I'd occasionally conversed throughout the ride. We had beer and sang Beatles songs, culminating in a rousing chorus of

"Yesterday."

The final morning, we awoke in a dense fog. I played more blackball with the English speakers and then the Mongolians in my compartment taught me Mongolian poker (a game that, at least for our purposes, did not require any betting).

In preparation for our arrival in Moscow, the Mongolians put on nice clothes. It was sort of like the end of summer camp: the last few hours of a brief, yet close and meaningful, friendship. Our bedclothes were collected, and our provodniki (the train staff) were tipped. Robyn, Sam, Guie, and I bought some pirozhki (little pastries filled with meat, potatoes, or whatever) when we stopped in Danilov. Everyone exchanged addresses. We looked out the window in anticipation of our arrival. I played a final game of blackball with Batsukh, Amrah, and Pakyet, who was in a silly mood. And then we reached Moscow, and it was all over.

|

28 Sep–2 Oct

Moscow

Rustam and his family; how to obtain a Russian visa; Moscow State

University; three fascinating museums; living it up at night...

|

Rustam, my friend for 10 years ever since we met on a United States–Russia exchange program in high school, met the arrival of my train at Yaroslav Station. He loves to play host, so he drove my English-speaking friends to the Rossiya Hotel, answering questions about the city in the comical, yet accurate, way that he always has. When we hit a traffic jam and someone asked whether it was peak hour, he replied, "Peak hour starts at eight o'clock in the morning and ends at eight o'clock at

night."

We went back to his apartment, where his parents, Masha and Anvar, and his cocker spaniel, Polina, greeted me. Shortly thereafter we had a dinner consisting of a meat-and-gelatin concoction (a quintessentially Russian staple), bread, salad, apple pie, and tea. Rustam and his parents live near Kiev Station, in the western part of the city center, in an apartment that has either two or three bedrooms, depending on what they're being used for and who's there. They recently acquired a washing machine, which Rustam and his brother (who now lives in the southwestern part of the city with his wife and child) gifted to their mother. Their apartment is on the fifth floor of a building carefully guarded by a 70-year-old babushka (the friendly face is more important than the security) and is reached by one of those neat elevators where you have to open the door

yourself.

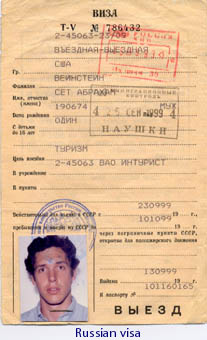

A long diversion is required to explain why, if I was staying with Rustam, I had to spend $67 for a night at the Ukraina Hotel. It comes down to Russian bureaucracy. In order to obtain a Russian visa, you must prove that you have accommodation booked for every night of your stay in Russia. A fax from a friend is not enough: You must either go through a visa-support agency (which involves booking a hotel room) or have a private invitation processed (which I'd have had Rustam do if I'd gotten my act together to plan this trip a couple of months earlier). Since all nights in Russia must be accounted for, multi-day train trips - such as the Trans-Mongolian - must also be pre-booked before a visa will be issued. Then, when you provide your proof of accommodation, your application form, and three passport photographs cut to precisely the required dimensions, they issue a visa. And once you enter Russia, you have to have your visa registered, which can be done only by the Russian organization associated with the visa-support agency that booked your hotel room. (This registration is usually handled by the hotel itself.) In other words, I had had to pre-book a few days at the Ukraina Hotel, as well as the Trans-Mongolian trip, in order to get a 10-day Russian

visa. A long diversion is required to explain why, if I was staying with Rustam, I had to spend $67 for a night at the Ukraina Hotel. It comes down to Russian bureaucracy. In order to obtain a Russian visa, you must prove that you have accommodation booked for every night of your stay in Russia. A fax from a friend is not enough: You must either go through a visa-support agency (which involves booking a hotel room) or have a private invitation processed (which I'd have had Rustam do if I'd gotten my act together to plan this trip a couple of months earlier). Since all nights in Russia must be accounted for, multi-day train trips - such as the Trans-Mongolian - must also be pre-booked before a visa will be issued. Then, when you provide your proof of accommodation, your application form, and three passport photographs cut to precisely the required dimensions, they issue a visa. And once you enter Russia, you have to have your visa registered, which can be done only by the Russian organization associated with the visa-support agency that booked your hotel room. (This registration is usually handled by the hotel itself.) In other words, I had had to pre-book a few days at the Ukraina Hotel, as well as the Trans-Mongolian trip, in order to get a 10-day Russian

visa.

All this may sound as if it could have been accomplished with a couple of phone calls, but it was a mind-boggling process. Everything had to be done in just the right order. There are not many places in the United States where one can buy a ticket on the Trans-Mongolian Railway; White Nights Travel is one of the few. After a series of phone calls, its friendly staff, in California and St. Petersburg, arranged for the ticket to be waiting for me at its partner agency's office in Mongolia. And I booked the Ukraina Hotel through Asla, a company based in England. First I booked three days at the Ukraina, which is how long I planned to spend in Moscow. Then, once Asla issued my letter of visa support (which I needed in order to obtain my visa), I had Asla cancel two nights at the Ukraina (leaving one night for the people at the Ukraina to register my visa). Asla was tremendously helpful through the whole process, and I didn't like putting it through all that rescheduling - but it was either that or fork over an extra $134 for the hotel room. Contacting Asla and White Nights during morning business hours in England and Russia involved waking up at 4:30 in the morning a couple of times in New York to make phone calls. And then, once I had all that visa support, I had the Russian Travel Bureau take it to the Russian consulate in New York (easier than dealing with the consulate directly). And thanks to Hurricane Floyd, the Russian Travel Bureau closed early on the day I was to pick up my visa, requiring me to rush over there during the

storm.

But back to our travelogue. Rustam dropped me off at the Ukraina Hotel before going to his job at Moscow State University for the evening; he was finishing up a project involving computer sound files. I checked in to room 503, leaving my visa at reception to be registered so that I could pick it up the following morning. I went up to the room, even though I wasn't staying there. It was beautiful, with an imposingly high ceiling and a good view of the Moskva River. It felt like the library of some mansion. I took a brief rest on the soft bed, and when I left I took a bar of soap.

|

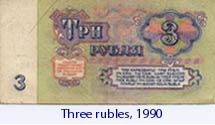

I walked along the Arbat, a pedestrian street, and marveled at how much the city had changed in the 10 years since I was first there. This was my third trip, and each time I'd come they'd had a different currency. They kept changing the street names and the names of subway stations as well. In 1990, the Soviet Union was just about to disintegrate, and the effects of an era of oppression were apparent, with nearly empty supermarkets, vacant restaurants that refused to accept customers without a bribe, and a devalued currency that made everything dirt-cheap for Americans. In 1994, the country was trying too hard to be western, with too much glitz and not enough prosperity. In 1999, I liked the place the best: The city retained all of its architectural and cultural charm dating from centuries ago, but it had emerged into a modern European city, with

cafes spilling onto sidewalks and more friendly faces than in the past - they were even starting to build attractive apartment

buildings. |

I had some ice cream and watched a jazz nonette playing outside. It consisted of three saxophones, a trumpet, a trombone, a string bass, percussion, a banjo, and an accordion. I walked to Red Square, which looked the same as always: a vast area dominated by the illuminated St. Basil's Cathedral and the tomb of Lenin. Well, maybe almost the same as always - there were no longer hour-long queues to visit Lenin's mausoleum, and there was a pretty garden with a fountain (Aleksandrovsky

Sad).

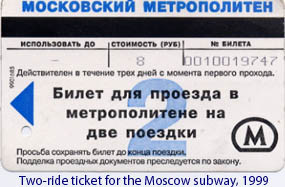

I walked beyond Red Square, not really knowing where I was going, and eventually I took a long walk along the Moskva River and then found the Taganskaya subway station. In 1990 a subway ride cost five kopeks (there were 100 kopeks in a ruble), and you just put your five-kopek coin (worth about a third of a penny) into the turnstile, or what looked like a turnstile except that nothing actually turned; if you tried to go through without paying, motion sensors would

cause the gate to close, and if it closed on your leg, you'd get five kopeks' worth of pain.

In 1994 a subway ride cost 150 rubles (kopeks were ancient history by then), and you had to buy green tokens. By 1999 they had upgraded to fancy magnetic cards, and rides cost five rubles, less if you bought

multiple rides. (Rustam said that when they first came out with the cards, people figured out how to copy the magnetic strip from one card to another, and they enjoyed free trips.) And the battered machines that used to change 10-, 15-, and 25-kopek coins were still there, even though they'd been unused for

years. In 1994 a subway ride cost 150 rubles (kopeks were ancient history by then), and you had to buy green tokens. By 1999 they had upgraded to fancy magnetic cards, and rides cost five rubles, less if you bought

multiple rides. (Rustam said that when they first came out with the cards, people figured out how to copy the magnetic strip from one card to another, and they enjoyed free trips.) And the battered machines that used to change 10-, 15-, and 25-kopek coins were still there, even though they'd been unused for

years.

As in the past, Rustam's family fed me as soon as I awoke, and then they kept offering meals throughout the day. Rustam went to work, and I walked around the inner city, through an affluent area near Kropotkinskaya, reading about the historical buildings in my Blue Guide to Moscow and Leningrad and admiring the yellow-and-white architecture dating back two centuries. (Yes, Leningrad. The guide was the one I'd used on my first trip to Russia, and while much of it was outdated, the walking tours were still valid.) There was a new cathedral in the city center, the Cathedral of Christ, Our Savior. It was beautifully gilded on the outside but clearly aimed at tourists. Inside were pristinely modern religious art, a few old icons, and a choir that occasionally sang in tune. In the chapel, a smaller building in the cathedral's garden, women were kneeling and praying - one clutched my arm to balance herself as she stood

up.

I went to the Archaeology Museum, which contained some interesting drawings of 19th- and 20th-century Moscow. There were also pretty paintings of Tobolsk (a Siberian city on the Ob River) by Vladimir Igrovnikov. I tried to have lunch at Praga, one of Moscow's nicest restaurants, but I was denied entry with sneakers on. So I went to the area around Kusnetsky Most, an area with expensive jewelry and clothing stores (except for the block in front of the Kusnetsky Most subway station itself, a seedy street smelling of urine). There was also a new pedestrian street, Theatre Row, lined with Tibetan, Italian, and other ethnic restaurants. I had lunch a few blocks away at the Orga Cafe, where I had the smoked fish and manti (meat dumplings) for RUB

230.

I met Rustam at the university, where he and a couple of co-workers were under the gun to finish a project in which they were synchronizing sound with film. It was not working, and while they tried to figure it out, I used their painstakingly slow Internet connection. After three hours, Rustam, eager to take a break, drove me home, and then he went back until the early-morning hours.

The next morning, with Anvar's help, I bought a train ticket for the Tisza Express, from Moscow to the Hungarian city of Nyíregyháza. The process of procuring the ticket brought me back to the Moscow of the past, as I had to stand in three queues - one to ask for the ticket, one to pay for it, and then the first one again to pick it up. Then, in Dom Knigi (a huge bookstore), I looked at Russian travel guides to Moscow and Russian travel guides to New

York.

I visited the Museum of Moscow History, which had a large, fascinating exhibit on the city's 850-year existence. There were ancient tools, coins, city maps, and toys, and a poignant section on post-revolutionary Moscow displayed ration cards, photos with faces of then-revered and now-denounced characters removed, and a picture of a girl holding bullets, captioned "Souvenirs of

1993".

Then I met Rustam at the university, and he treated me to dinner in a café and took me home. He was too tired to go out for the evening, but I'd seen a piano bar in the Kusnetsky Most area and wanted to check it out. It was called Stary Royal (The Old Piano), and it was on the fifth floor of a building that didn't have much going on on the other floors. When I arrived, however, only a few people were there, and there was no music being played - a bartender explained that the music didn't start until

November.

As is the case with many of the things I do, going to Stary Royal had a dual purpose. I also wanted to check out a place next door, a club called the Hungry Duck. My motive for going there was inspired by the colorful review the place got in the Time Out guide to Moscow - a review that mentioned, among other things, the people dancing on the bar and the tables; the fact that at least two patrons, whether by choice or under the influence, are likely to shack up each night; the pool of indistinguishable fluids that must be cleaned up after the place closes; and the periodic ladies' nights, on which women are served for free and admitted earlier than men, to give them a head start on the intoxication process. I didn't want to be there when it was at its rowdiest, but as a man who loves extremes, I had to - at least - go

inside.

Cover for men that evening was RUB 100; cover for women was RUB 25. After I paid and underwent a search for weapons, I ascended a staircase that led to a large, dimly lit room. There was a central bar area surrounded by a dancing area, and along the walls were tables and seats. The back room was more brightly illuminated and had another bar and more seating. It was early, so there were only a few people there, but as if by decree, some of them were already atop the tables, and one man was easily coerced into taking his shirt off. I had a Heineken (RUB 90) and watched the place start to fill up.

The best aspect of the place was the music - the DJ played the most melodic disco tunes I'd ever heard (not that I am that well acquainted with disco tunes). Sadly, I couldn't stay long, because I had to return to Rustam's before the building was locked at midnight. But the brief visit was well worth the

trip.

Masha made pancakes for breakfast the next morning, and she served us a delicious fruity kefir (yogurt drink). Then Rustam took me to the Novodevichy Convent, an attractive complex originally built in the early 1500s and reconstructed in the late 1700s. In its cemetery rest notable writers, artists, and political figures, including Gogol, Chekhov, Scriabin, Prokofiev, and Khrushchev. It was near the university, and Rustam liked to go there as a respite from the bustle of the city. Indeed, it was quite pleasant, with fortress-like buildings, a pretty chapel, attractive gardens and lawns, and a pond.

From there, we drove to Kolomenskoye, a country estate located in the southeastern outskirts of the city. It had one large, impressive church; a small, intimate church; an imposing gate; and sweeping views of the Moskva River. Rustam and I had some blini in the café before heading to the university.

That night was our big night out. Rustam and I met five of his friends near a centrally located subway station, bought some bottles of Stary Melnik - a Russian brand of beer - from a kiosk (I appreciated the ability to walk down the street legally chugging a brewsky), and headed to a club called Crisis Genre (no one could come up with an explanation of that name), leaving empty beer bottles on the street so that poor babushkas could collect them and turn them in for a

refund.

Crisis Genre was packed, and the Crossroads blues band played for much of the evening. A few other friends joined us throughout the evening, and the pitchers of beer kept coming. I couldn't down much of it, as my stomach didn't feel like dealing with all that fizz that night. Much later on, a few friends came back to Rustam's place, where we had vodka (I didn't go for much of that either) and scraps of whatever food happened to be in the refrigerator. And because Rustam loves to play host, seven guests stayed in the apartment that

night.

The next morning, while the others slept off their booze and vodka, I visited the Museum of Music, a place that had been closed when I'd tried to go in 1994 (many Russian museums close during the summer). There was a good exhibit featuring Arensky scores and a massive collection of instruments from all reaches of the world (especially the former Soviet republics). The two most bizarre, I thought, were the the duda (a Czechoslovak instrument that looked like a bagpipe, two horns, and a stringed instrument all connected somehow) and the chimta (a Pakistani instrument that resembled a giant pair of

tweezers).

Since I'd be leaving for Hungary that night, I stocked up on snacks at a supermarket near Rustam's place. I got some nondescript cheese, deli meat, banana-apple juice, and salmon caviar - and I bought some osetra caviar to take back to the United States. When I returned to Rustam's apartment, I joined the others for lunch: Anvar had made plov (an Uzbek rice-and-meat stew). Then a bunch of us visited the botanical gardens at the university. They were closed to the public, and we had to scale a fence in order to get in, but it was worth it for the impressive display of trees from all over the world. A caretaker who came by didn't seem to care that we had somehow gotten

in.

Rustam and I returned home for another meal, and Masha gave me some snacks for the train ride, including a veal-flavored soup mix that I never got around to using and that didn't make it past the agriculture check at the airport in Philadelphia. I exchanged a bunch of rubles back into dollars (for certain, the currency would change again by the time I'd next be in Russia) and, true to fashion, boarded the train at Kiev Station just three minutes before departure.

|

2 Oct–3 Oct

Train: Tisza Express # 15, Moscow to Nyíregyháza

(21:07; 10h 28m to Konotop; RUB 2033.20)

|

What a nice train this was! I was the only one in my stately, spacious

compartment, which had pretty wood paneling and a surplus of linens. The

conductor tried to get me to switch to a middle birth in another compartment,

but I made it clear that I much preferred my lower birth. It did not take long

for me to fall asleep.

I awoke at around 6:30 Ukrainian time (an hour behind Moscow time) the next

morning, just as the train pulled into the station at Konotop, the Ukrainian

border town. Customs officials boarded, and that's when the trouble started.

|

3 Oct

Konotop (Ukraine)

As my uncle said, "Konotop this!"

|

"Where is your Ukrainian visa?" asked the no-nonsense

official in her shrill voice, after she leafed through my passport.

"I don't have one."

"You don't have one?"

"According to the Ukrainian consulate in New York, United

States citizens don't need a transit visa to pass through Ukraine."

"Gather your things."

I'd been given out-of-date information: Since sometime in

August, she explained, the rules had changed, and I'd not thought to call the

Ukrainian consulate, um, er, every day while I was planning my trip.

(When I returned to the United States, my father suggested that

perhaps she had been looking for a bribe. He referred to an article he'd read

in which a group driving through Ukraine had had bribes extracted from them

several times. The possibility of a bribe hadn't occurred to me in the heat of

the moment, and even if it had, I'm not sure I'd have had the guts to offer

a bribe to a customs official.)

Gathering my things did not take long, as I had only one bag.

She and her companion took me into the customs building, where I sat in a room

with a bunch of customs officials and watched one of them try to fill out

whatever form it was that explained why I was there and what they were to do

with me. Using a previously completed form with the word "Protocol" at the

top as a template - perhaps the form completed for the last person escorted off

the train - , this official (different from the first one I'd met) copiously

filled in every detail and wrote paragraph-long explanations in her pristine

handwriting. I was repeatedly asked where I worked, though I never actually gave

the name of my company. And lest you think they had all the fun, I also got to

complete a form - in Russian - explaining why I didn't have a visa. But the

most fun of all was watching them try to spell "Massachusetts," which is

where my passport was issued.

After about an hour of that, a relatively elderly man (most of

the officials were young) collected a $25 fine from me, and then I talked with

another official about life in New York. And he shared some information about

his family.

"You see that woman over there?"

"Yes."

"That's my wife."

Ah, so that's what it's like to be married to a customs

official. You've got to be one yourself.

Then another man escorted me to a dim hallway, where I would

wait until the next train came to take me back to Russia - at 22:30 that night.

"Is there a bathroom?" I asked.

He showed me where it was. I used it; then I returned to the

hallway and sat down.

"Is there light?"

He flicked a switch in the hallway, but the light didn't come

on. He shrugged and walked away.

I did not stand up for the next ten hours. I wrote a letter to

my girlfriend and read Riding the Iron Rooster. I ate deli meats and

cheese and caviar and drank banana-apple juice. I perused my guide to Hungary

and planned my days in Budapest and Eger. And I did not make a sound.

|

3 Oct-4 Oct

Train: #90, Konotop to Moscow

(22:30; $15; 10h 19m)

|

Again, I had my own compartment. Shortly after the train left, a short, stout, grumpy-looking, cigar-smoking conductor entered. He seemed archetypical for his job - he was elderly and looked as if he'd been a conductor on this very train for 100 years. For most of this, or any, conversation, he kept his cigar in his mouth, scarcely removing it to speak, and rarely uttering more than four words at a

time.

His duty was to get me out of Ukraine, and he didn't really care what happened then. Thus, the trip from Konotop to the first Russian town, Bryansk, would be free, and it would cost me $15 to go back to Moscow. Before he left, he asked if I wanted more blankets. I replied that I was fine. With an Ed Norton–like shooting-the-cuff arm gesture, he said the Russian equivalent of "If you're OK, I'm OK." Then he was

off.

Once we left Bryansk, an official came to inspect my Russian visa. Fortunately the consulate in New York had given me a couple of extra days (beyond those for which I'd proven confirmed accommodation), so it was still valid. That's also when I realized a loophole in the whole visa-registration nonsense: On the train trip out of Russia to Ukraine, no one had checked my visa or stamped me out of Russia, so it wouldn't have mattered if I had failed to register it - or, for that matter, stayed a few extra days beyond its

validity.

Then I had the night to myself. The window was ajar, but I did not close it; the howling wind and the rattling wheels gave the effect of out-of-control, reckless passage - which I felt appropriate for the circumstances.

|

4 Oct

Moscow

Rushing about...

|

Having lost two days, I ran to a travel agent to see about cheap flights from Moscow to Budapest that day. The agent only sold Aeroflot tickets, and I wasn't too keen on flying Aeroflot. So I ran to the office of Malév (the Hungarian airline). There was a flight at 14:30, but it cost $299.20 - and given my preference for trains, I didn't want to spend that much to fly. So I ran back to the Aeroflot place to see how much that flight cost: $306, and it wasn't until the next

day.

So I ran to the Ukrainian consulate to see whether I could get a same-day visa. I could, for $105, and I'd have to get the application in by 13:00. So I ran to a quickie-photo place to get a passport photo, and I turned in my application a few minutes before the

deadline.

When I presented my application to the consular official, I explained that I needed a same-day visa and that I'd been turned away at the border even though the Ukrainian consulate in New York had indicated that I didn't need a transit

visa.

He went away for a few seconds to investigate this pecularity. I was hoping he'd come back with some huge apology and an offer to somehow compensate me for two days' travel

lost.

"Yes, you need one," he replied. Ah, how helpful.

Then there were two problems. First, I didn't actually have a ticket from Russia through Ukraine to Hungary, which I officially needed in order to get a transit visa - I had only the part from Ukraine to Hungary, as they'd lifted the first part. I explained that I would go to the ticket office to buy the

ticket.

Second, I had no blank visa pages in my passport.

"What does this say?" he said, pointing to the only blank page.

"Amendments and endorsements."

"Where am I supposed to put the visa?"

"Please...."

Fortunately he overlooked both problems. He accepted my application and told me to come back that afternoon to pick up the

visa.

I had a spectacular lunch at Aragvi, a Georgian restaurant. The place was beautiful, with marble walls, paintings, and a fountain; my lunch was black caviar, chanakhi (a wonderful-smelling meat-and-vegetable soup), amirani (pork with hot apples), and two Cokes, for RUB 780 (including a small charge for butter). Then I got some ice cream and looked at travel guides in a bookstore until it was time to pick up my visa.

The person who had the job of admitting people into the Ukrainian consulate was surprised to see me again - he thought I'd erred in thinking my visa would be ready the same day. I guess people don't fork over the cash for same-day visas very often. But the visa was ready for me, and though $105 was a lot to have spent on a visa, I must say that, with its silver hologram, it was the prettiest visa I had ever

obtained. The person who had the job of admitting people into the Ukrainian consulate was surprised to see me again - he thought I'd erred in thinking my visa would be ready the same day. I guess people don't fork over the cash for same-day visas very often. But the visa was ready for me, and though $105 was a lot to have spent on a visa, I must say that, with its silver hologram, it was the prettiest visa I had ever

obtained.

At the train-ticket office, I replaced the Moscow–Konotop portion of my ticket (RUB 363.20), and then I took the subway to a random part of town (Krasnogvardeyskaya, if you're counting), just to see what was there, to pass the time until my train left. There was a large supermarket at Krasnogvardeyskaya, and I bought some more caviar, as well as nectarines, water, and peach juice. Then I returned to Kiev Station.

|

4 Oct–6 Oct

Train: Tisza Express #15, Moscow to Nyíregyháza

(21:07; 37h 16m; arrived 30m late; RUB 2033.20)

|

Once again, I was alone in the compartment, at least for a while. I wondered if I'd see any of the same customs officials when we reached Konotop, and I hoped I'd get to present my passport and visa to the same shrill official and show off my expedience. But I did not recognize any of the officials at Konotop. I was still subject to untoward scrutiny at the border town, and a short distance into Ukraine I was forced to spend $6 on health insurance in case any emergencies developed during my 24 hours in the

country.

Andrey, a recently married Ukrainian who shared my compartment from Kiev to Tyornopol, restored my belief that not all Ukrainians are money-extorting bureaucrats. He bought us sausage sandwiches and vodka. We discussed conditions in Ukraine since the collapse of the Soviet Union: He had thought life would improve, but he'd seen little evidence that it had, and he wondered where all his tax money was going. When he departed, I napped a short while, and then an American who spoke little English joined me in my compartment in Tyor. We both slept the

night.

I awoke at 4:16, when we arrived in Chop, the last Ukrainian town before the Hungarian border. Again came a series of questions from Ukrainian customs officials. Then the train was raised so that the bogies could be changed - the railway gauge in Hungary is a different width from the gauge in Russia and Ukraine. Finally we entered Hungary, and the train approached the border town of Zahony with apparent caution; the wheels made a loud, metallic "ping" sound every time they spun

around.

Zahony is where the delay was. There was no explanation - we just waited, and we got half an hour behind. We stopped at a small station that didn't seem to have a name, and, afraid of staying on the train too long, I asked the conductor whether we had reached Nyíregyháza. That one was Kisvárda: Nyíregyháza was next.

Go on to

part 3

|

|